Weather & Climate, Together Again

This story is set in the past and in the future. Let's start with...

THE FUTURE

In September, the World Meteorological Organization gathered local weather reports from over a dozen countries. Although they featured well-known weathercasters (including Jim Cantore at the Weather Channel), these reports were unusual, to say the least...

...because these are forecasts of storms, heatwaves or floods that take place in the year 2050. Organized with the help of the climate-focused non-profit Climate Central, this is a rare and successful effort to connect weather and climate in the public’s mind. Here are all the 2050 videos, whose contributors range from Brazil to Burkina Faso.

This effort was rare because the science of weather reporting, called meteorology, is focused on what the weather will be this week. Climatology is focused on weather patterns over a decade or a century or a millennium. The difference is partly responsible for a mini-scandal that took place a few years ago.

THE PAST

In 2009, climate-change deniers hacked the emails of climate scientists; the results of this so-called ‘Climategate’ are still playing out in the courts.

A few phrases used by the scientists in their emails, presented without context or explanation, appeared to imply that scientists were conspiring with each other to falsify data. Even if some climate scientists are shown to have exaggerated, the claim that climate change is false has ultimately been proven to have no merit. But it set the stage for a rift between climate and weather science.

In 2010, a survey of TV weathercasters revealed that Climategate had tipped many meteorologists into the skeptical category. This wasn’t difficult because the reliance on computer models by both disciplines has divided them: computers have greatly aided forecasters to predict local weather, but only up to 10 days or so into the future. How could computer models, they asked, show the weather so far in the future?

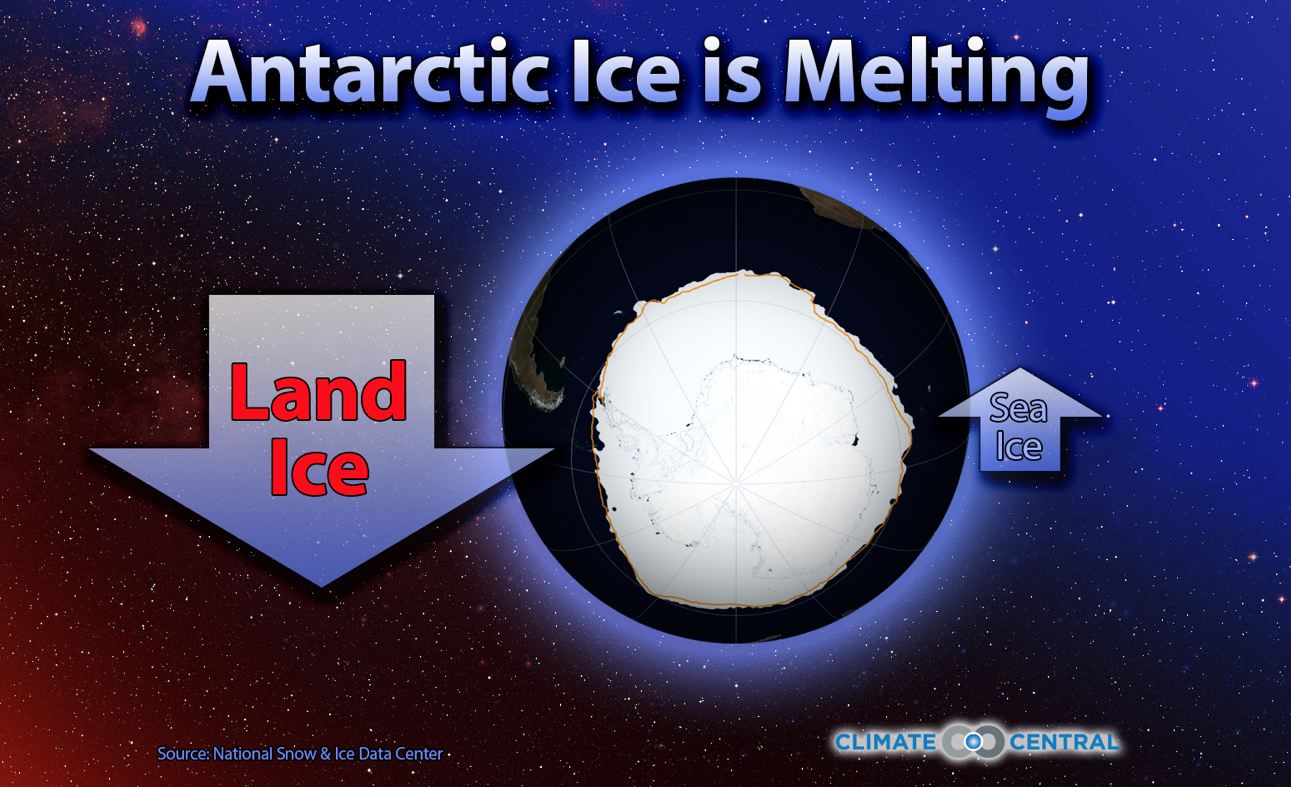

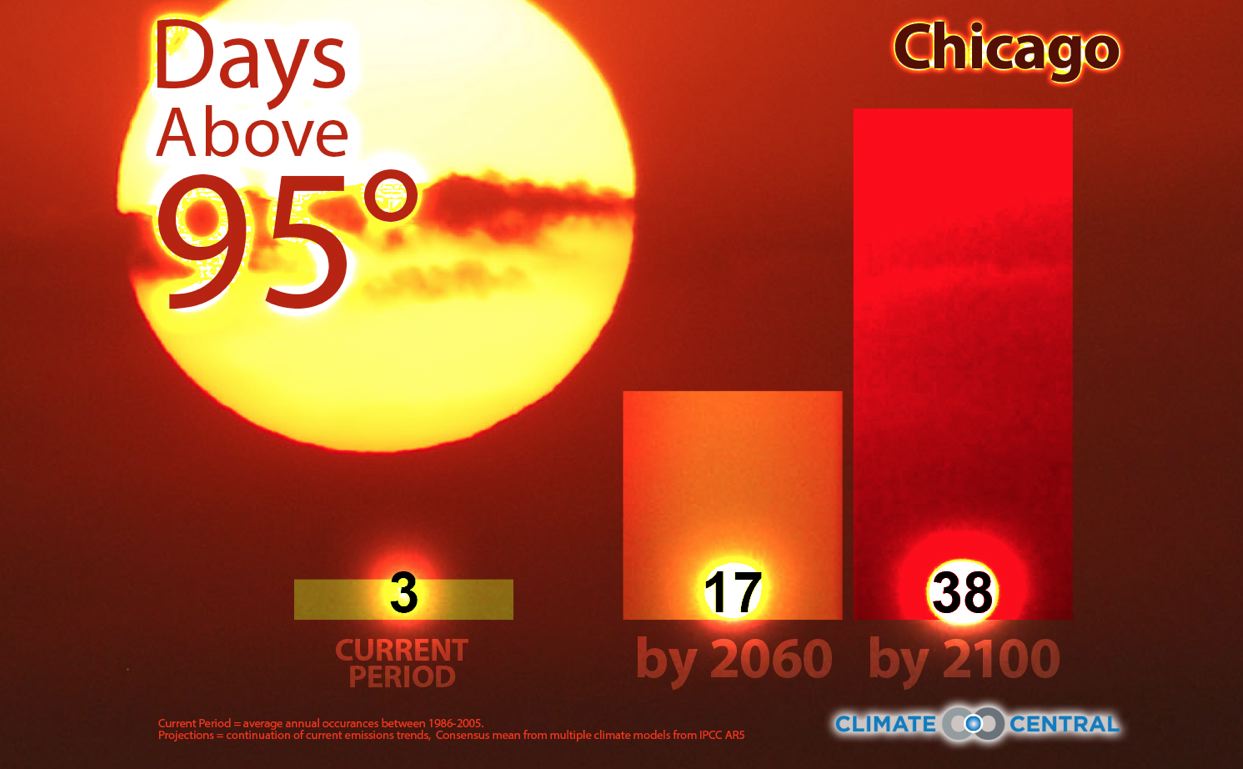

A 2011 study revealed that meteorologists didn’t have clear information depicting the long-term trends that reveal steady warming and other patterns related to cimate change. TV meteorologists in particular needed this evidence, presented in a highly visual way, to share with their viewers.

Here’s where Climate Central comes in again: their Climate Matters project creates graphics that are both TV-friendly and scientifically accurate. And a 2014 survey shows that TV weathercasters have more open minds about climate change today than in the past.

A new episode of This Planet, Weather & Climate & The Future, includes more about Climate Central's work, as well as an interview with their TV meteorologist, Bernadette Woods-Placky.

With 20/20 hindsight, a non-professional in weather and science like me wonders whether scientists and communicators relied too much on computer-generated climate models to alert the world to the dangers of climate change. As Climate Central has shown, events in the past may be more effective than those in a theoretical future to convince people that dumping endless amounts of carbon into the atmosphere has real consequences. And relying on real data rather than conjectures has an additional benefit: scientists are inoculated against accusations of fraud every time there’s a snow storm.

••••••••••••

PS (12/2/14) - Before we move on, I want to emphasize how Climate Central's focus on the sweet spot between climate and weather keeps yielding great information. Like the thorough coverage of today's rainstorm in California, which includes this sensational gif:

..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................